This Land is Your Land

Recognizing the people and nations that existed long before my own

Published: 20 Apr 2021

Topics: Life, Travel, History

TL;DR: Native Americans have lived in Colorado for thousands of years, while I’ve lived here for five.

A Time for Change

Over five years ago, my wife and I packed up the contents of our apartment and in classic American style, rented a U-Haul truck and drove west with our young son.

We were moving from Springfield, Missouri to Denver, Colorado for more opportunities; both professionally and personally. It was time for a change. It was time for a new challenge. It was time to get out of the state where I was born.

A Land of Water and Ridges

Once settled in, I started riding my bike on the greenway paths that are laid out along the various creeks and rivers in the area. As I quickly learned, it rarely rains in Colorado, yet there are many creek beds and rivers that shape the landscape due to snowmelt every year.

Being from Missouri, I had never really thought about water before: I was always surrounded by rivers, creeks, and lakes. But Colorado is very different; it is a high-desert and water is a precious resource where water rights are hotly contested.

As I rode along these creeks, I started thinking about those who lived on this land before me. The landmarks of the gold rush are all around these paths (in fact I often see people panning for gold in the creeks as a hobby) but what about the native people before the rush to strip the earth of resources?

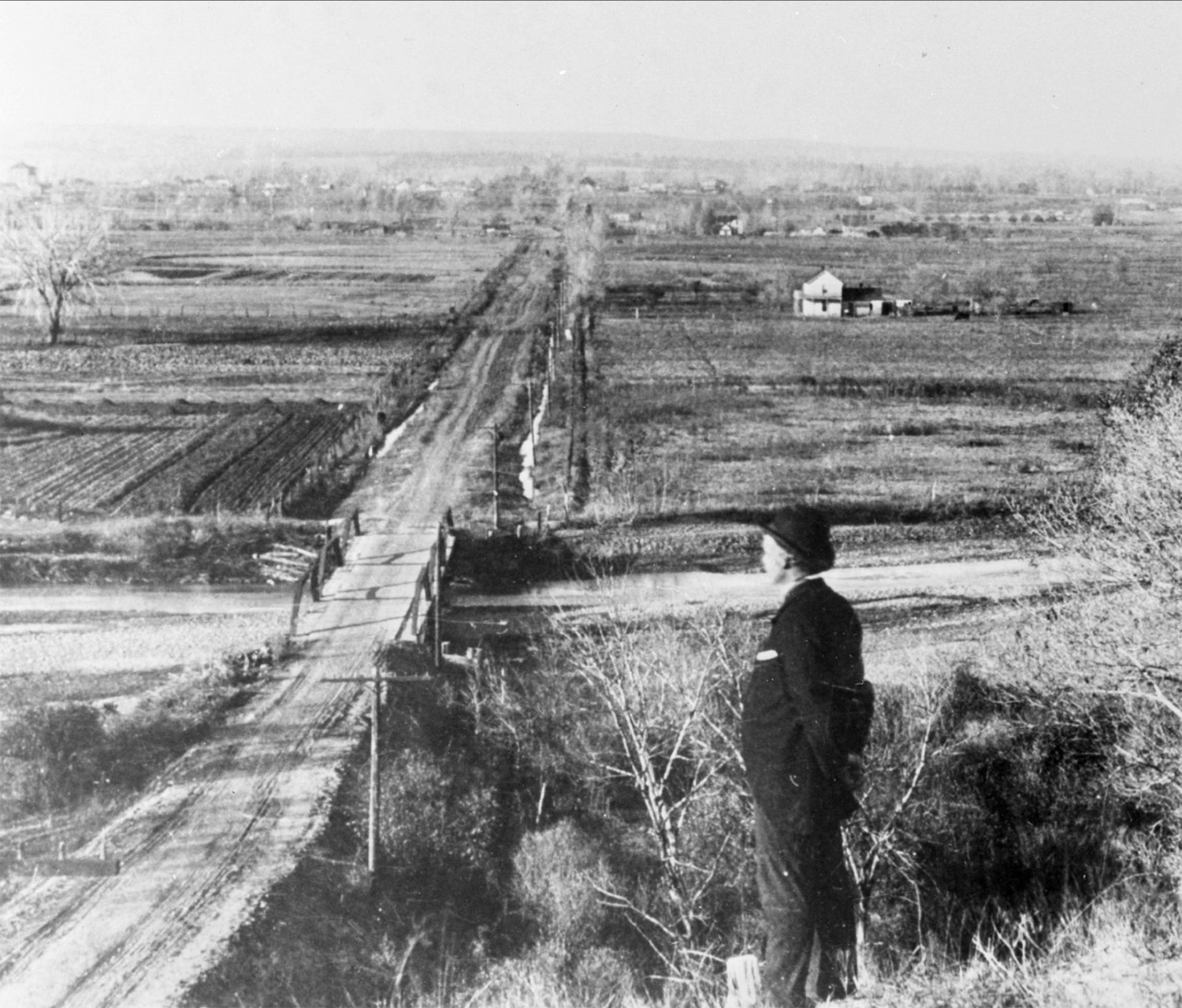

The town where I live, Wheat Ridge, is literally that: a ridge above Clear Creek that was used mainly for farming before becoming a town. Standing at the top of the ridge overlooking the creek and Interstate 70, I can easily imagine native people staring at the mountains out to the west just as I do today.

A Meeting Place of Many Tribes

Due to the importance of rivers, the confluence of Cherry Creek with the South Platte River (where Denver is today) seems to have always been a meeting place of the Ute people from the mountains along with the Arapaho and Cheyenne tribes from the plains.

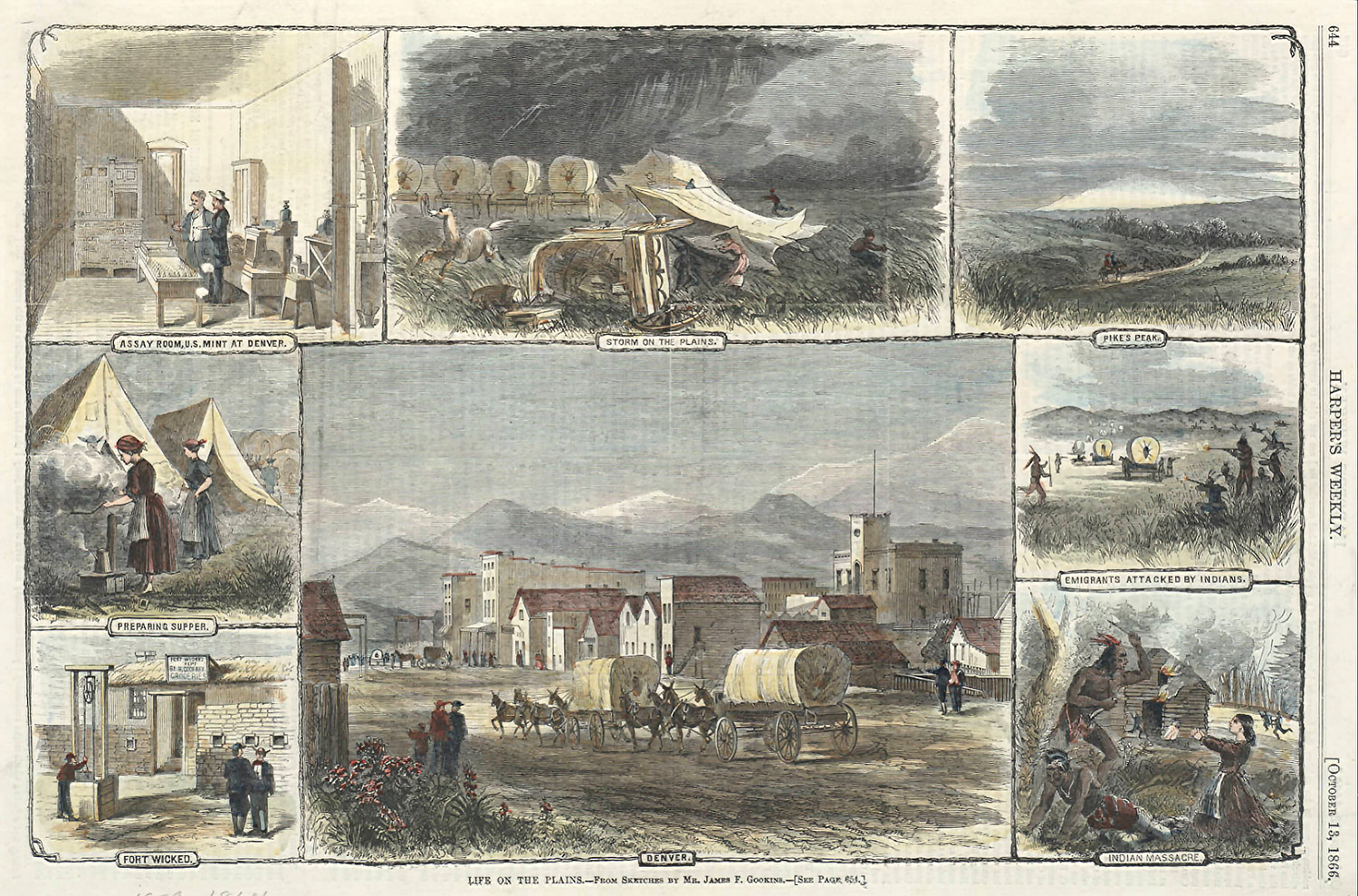

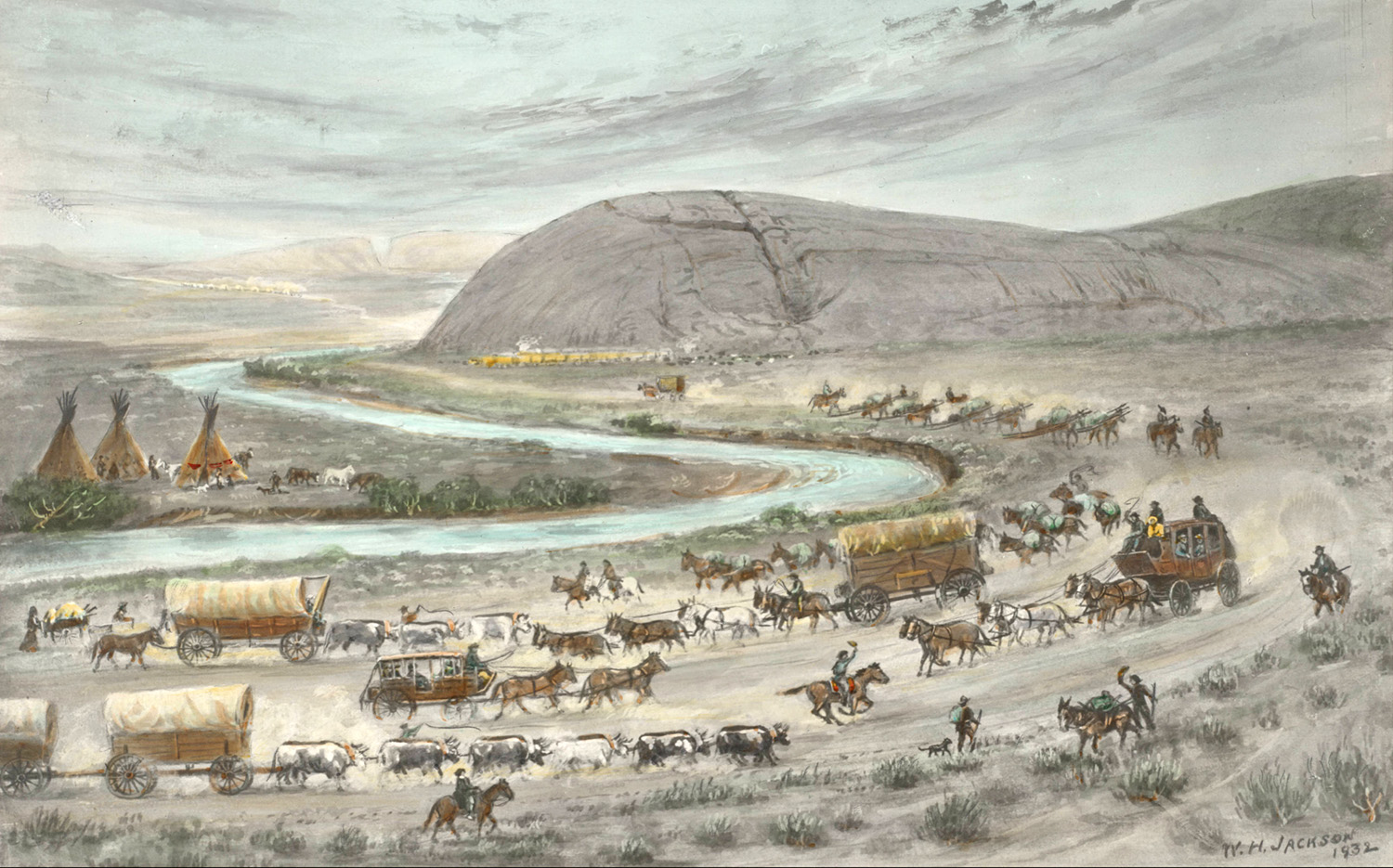

As white settlers pushed west in the 19th century searching for gold or more verdant farmland, they intruded on the lands of the Native Americans. Tensions invariably began to rise as they competed for resources while settlers used any method possible, including purposely slaughtering bison to starve Native Americans into submission and relinquish their land.

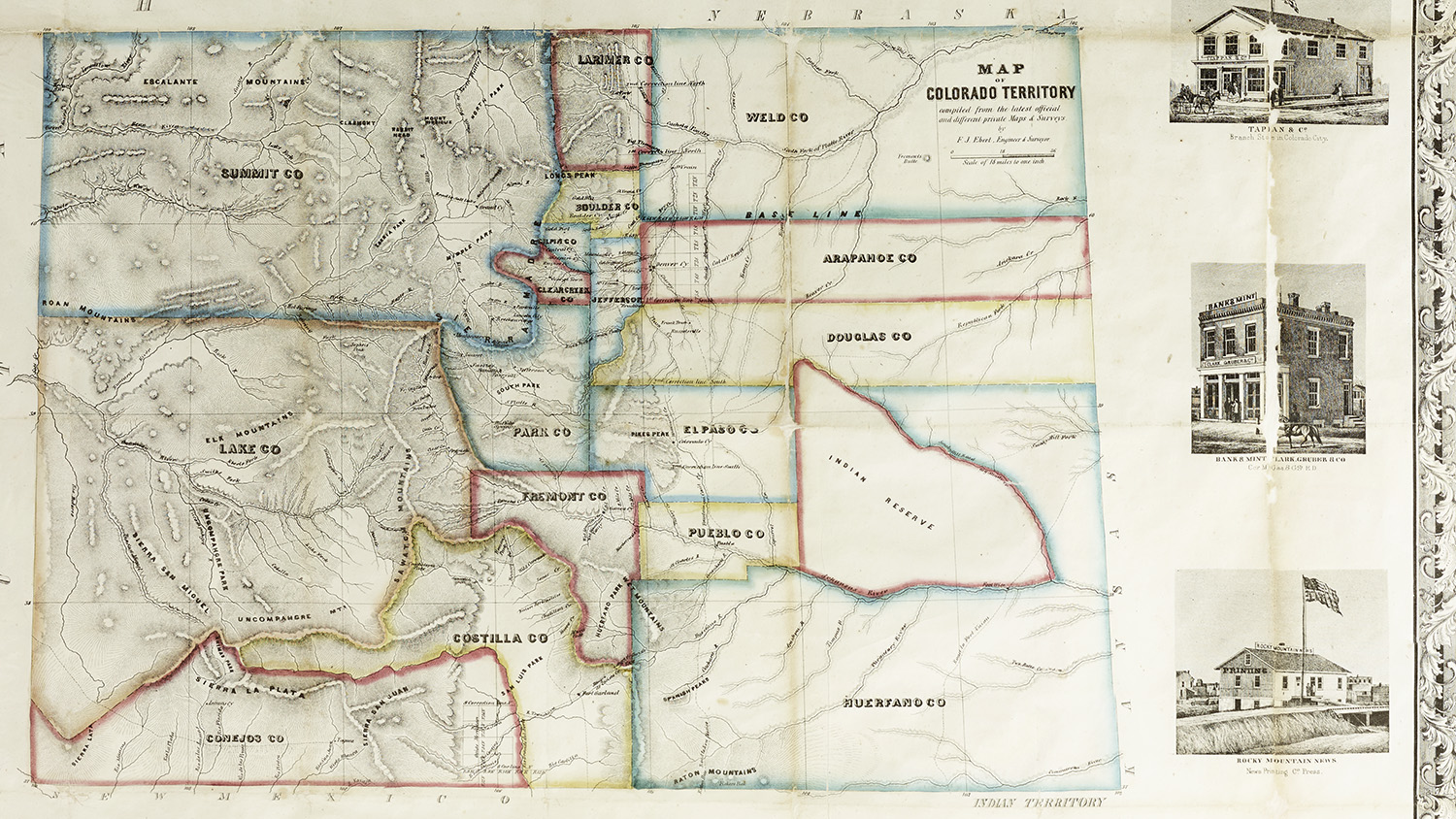

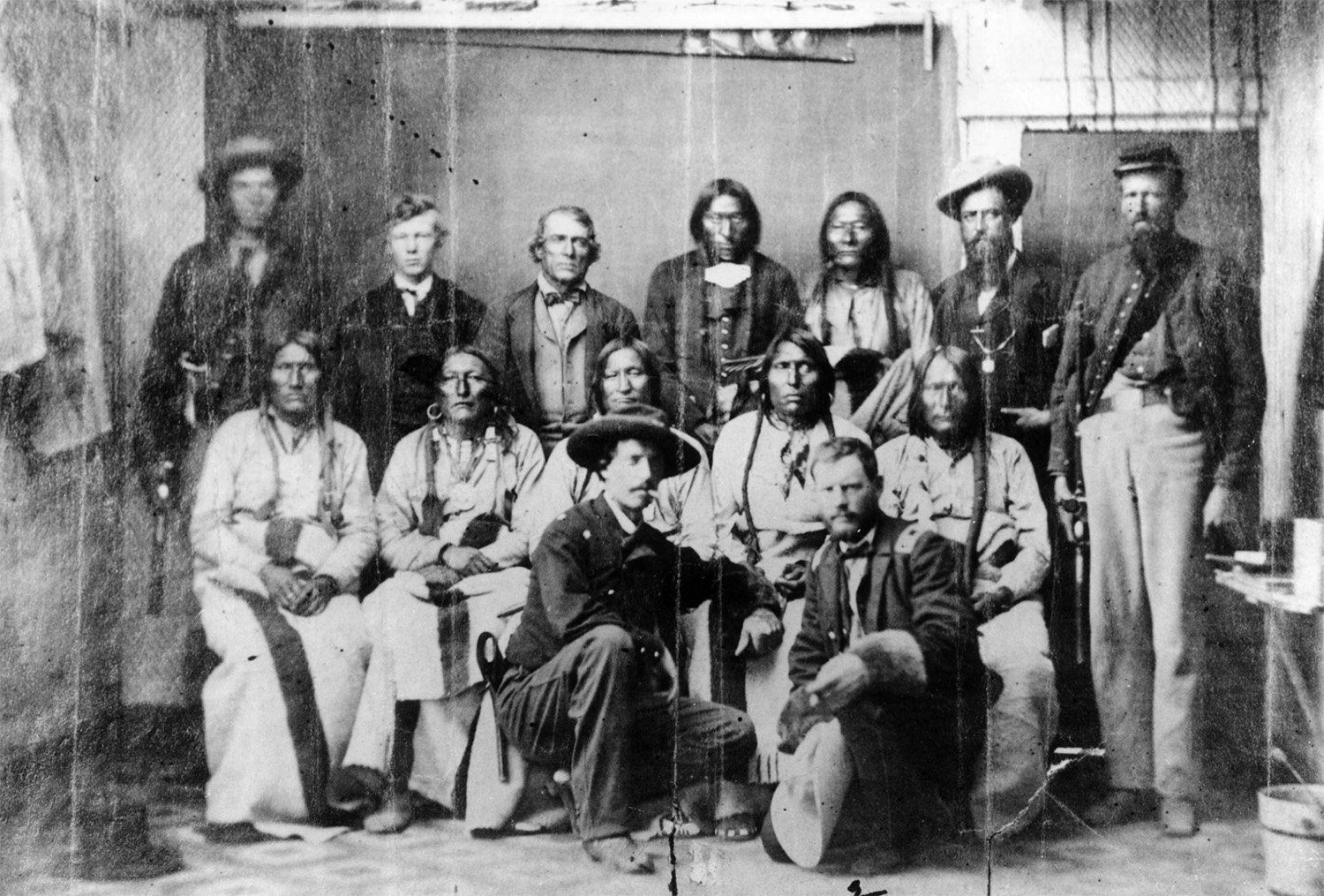

The Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851 granted federally-recognized land between the North Platte and Arkansas rivers (which includes parts of modern-day Wyoming, Colorado, Nebraska, and Kansas) to the Arapaho and Cheyenne tribes. This territory encompassed over 44 million acres including almost the entire Colorado front range.

In exchange for allowing travelers to pass freely through their lands along the Oregon Trail, federal representatives guaranteed the Native Americans an annual payment for 50 years (reduced to 10 years by the US government before they would ratifiy it) along with protection from settlement.

As with many other treaties made with tribes, the treaty was rarely enforced: supplies seldom arrived and when they did, they were often spoiled or the funds stolen by the government representatives themselves.

Gold, at Any Cost

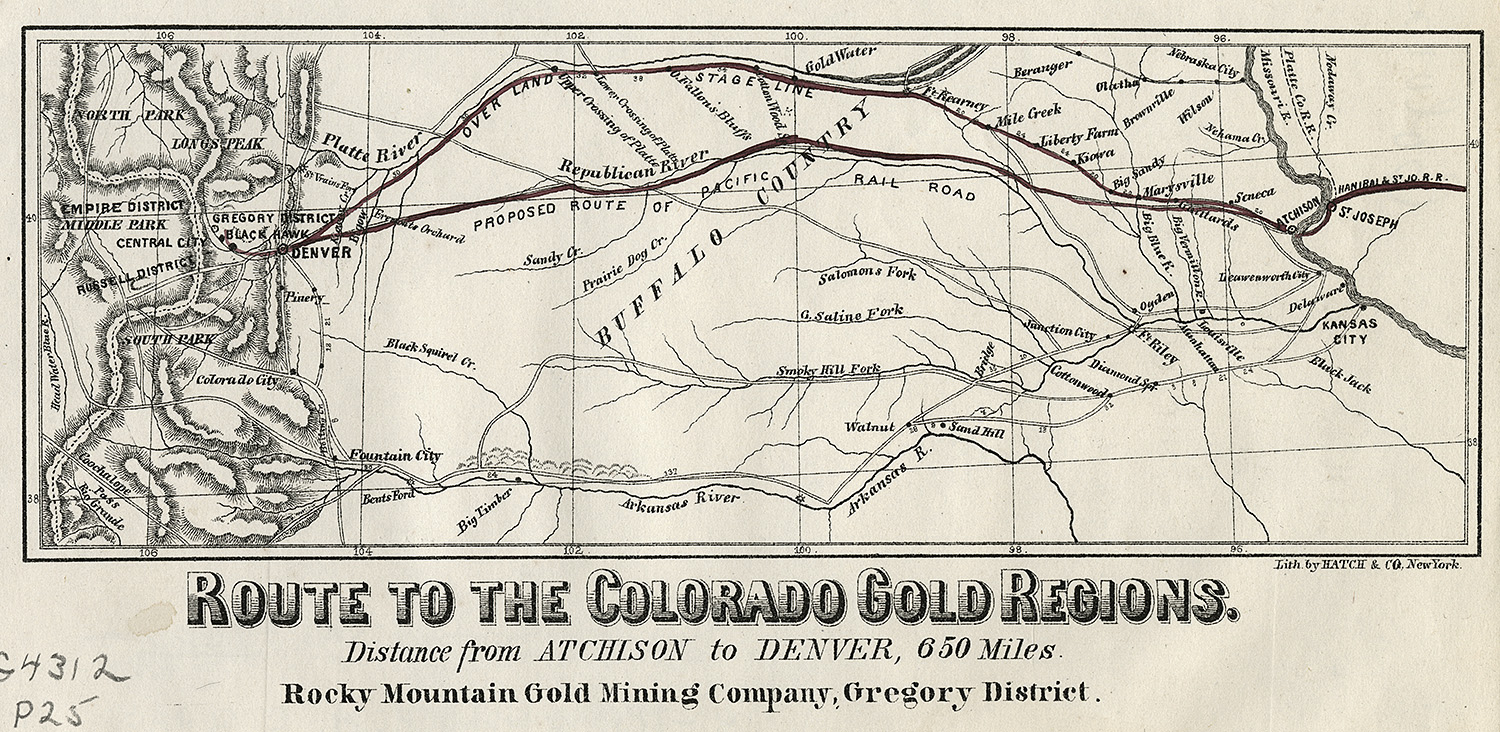

A decade after the gold rush in California, gold was discovered in Colorado. By 1859, thousands of miners and settlers invaded the land with the phrase “Pikes Peak or Bust!” staking claims and building the early communities of Denver, Golden City, and Boulder.

By 1861, settlers were demanding that the federal government recognize their mining claims instead of removing settlers (as promised by the earlier treaty). Due to this pressure, the Treaty of Fort Wise was signed by a minority group of Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs.

The legitimacy of this treaty was instantly in debate as many Cheyennes claimed it was signed without the approval of the whole tribe and the chiefs had not understood what they signed. The treaty drastically reduced the tribal territory from 44 million acres to 4 million acres between Big Sandy Creek and the Arkansas river.

The theft of such a large area of land in just 10 short years set things in motion for the Colorado War and tragic Sand Creek Massacre in 1864. Soon after, the remaining people of these Native Nations were relocated out of Colorado completely.

Knowing Where I Stand

I believe that only by facing the truth and learning from our collective past can we move forward into a more equitable future. America’s relentless western expansion and vulgar belief in Manifest Destiny displaced and destroyed cultures that have never been repaired or compensated.

I support reparations and Just Transition for indigenous people and continue to seek out the stories of the past.

Additionally, I’ve added a small amount of text on my website to acknowledge that the land on which I stand is not mine. This statement isn’t much, but it is a start.

Learn & Act

Knowing and understanding the history of the land where you live is important. If you live along the front range of Colorado, I suggest watching this documentary about westward expansion and the Sand Creek Massacre to understand the local history. Also, the video below about the Ute people helps explain the history of the western part of Colorado.

No matter where you live, a good first step (as it was for me) is to visit Native Land and enter your address to learn the territories, languages, and treaties that overlap your area.

After that, I suggest reading their Territory Acknowledgement Guide to see if you feel compelled to acknowledge and act.