Typographic Telegraphic Commercial Codes

These mysterious codes were designed to save money and reduce confusion

Published: 15 Jun 2021

Topics: Typography, History, Technology, Linotype

TL;DR: When telegrams were common, commercial codes saved money, reduced confusion, & cheated the system

Strange Codes & Asking Questions

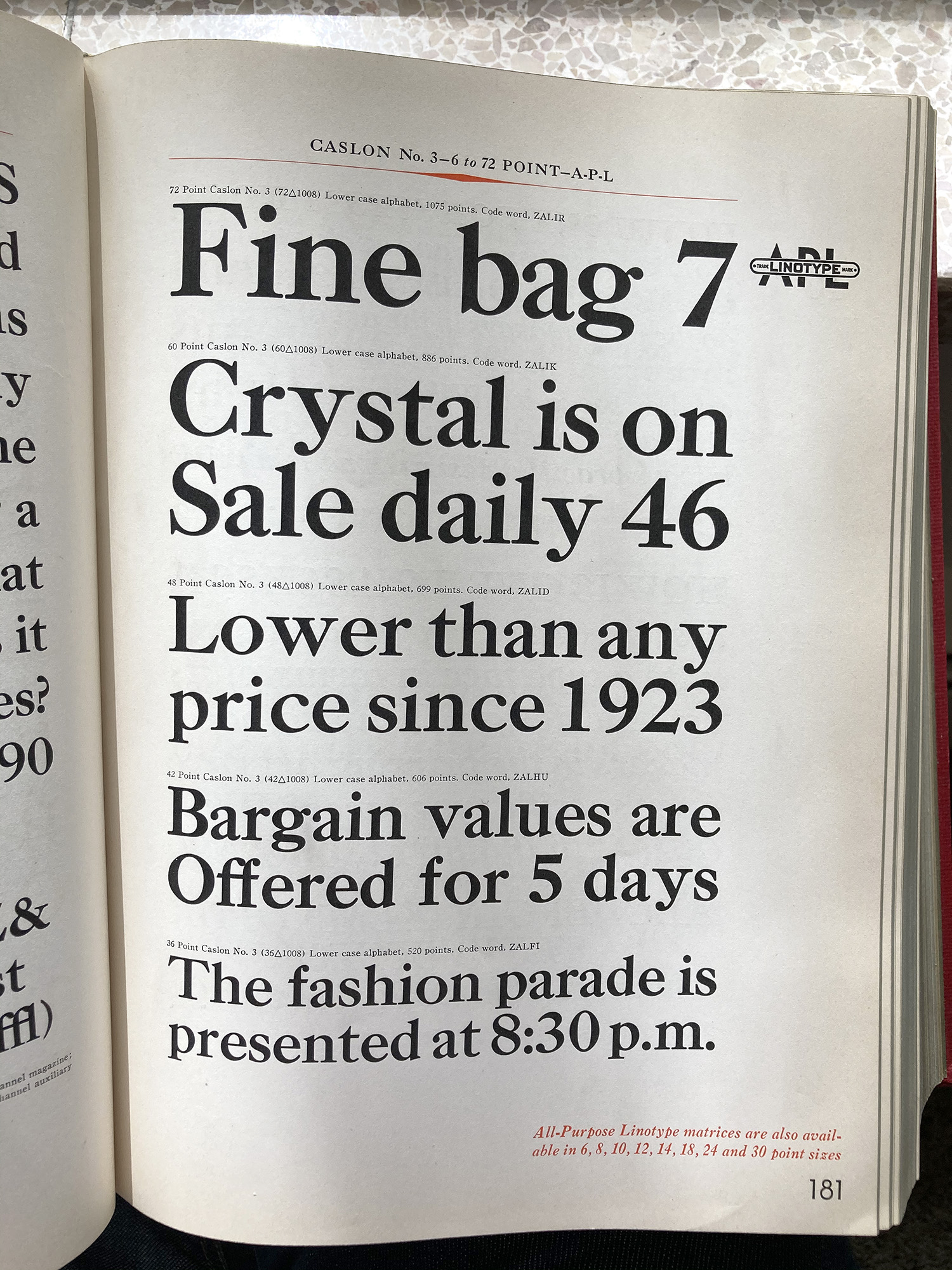

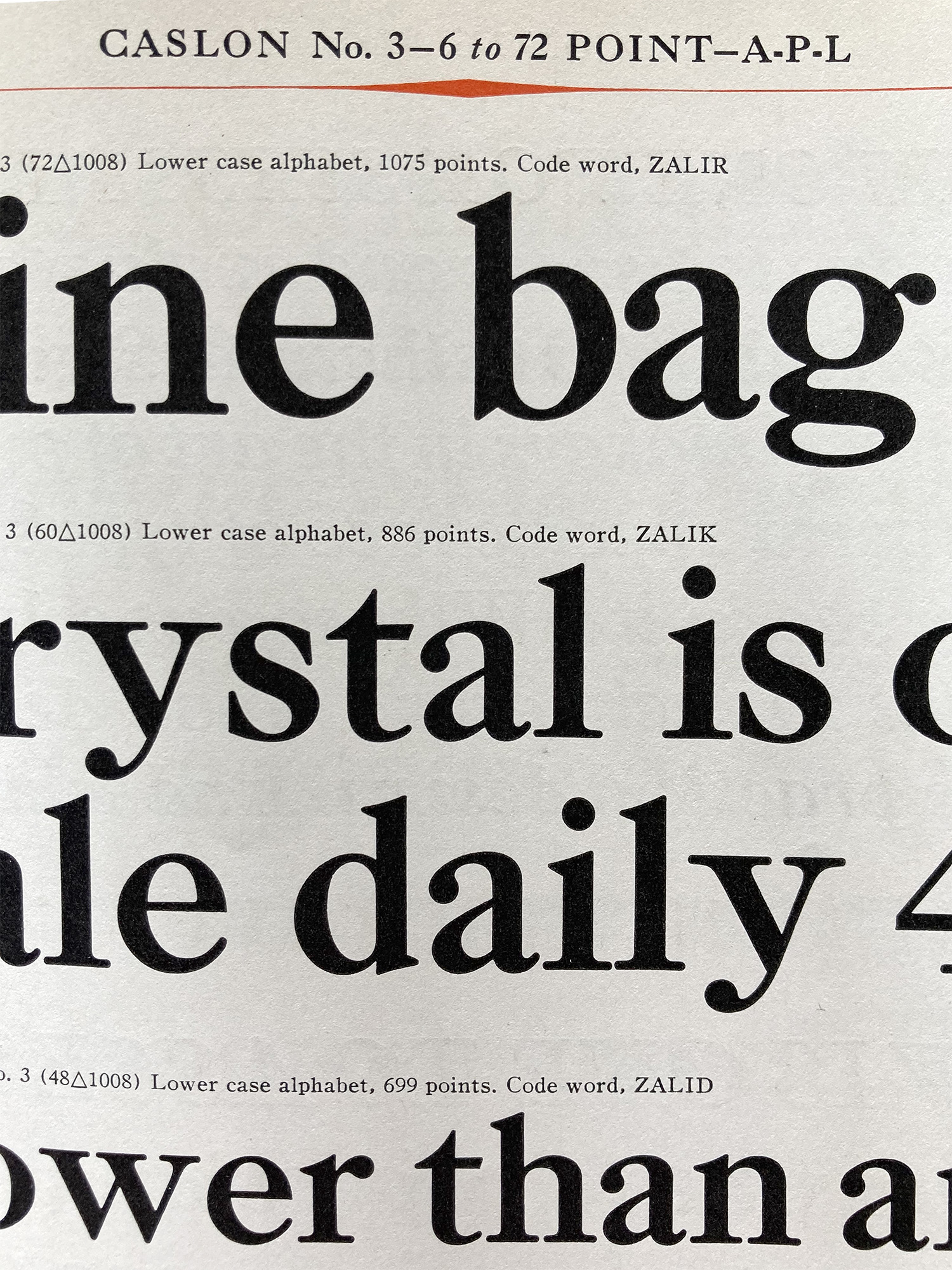

Like most designers and type nerds I know, I spend a fair amount of time poring over type specimen books; noticing the details of characters and the interesting ways that designers solved aesthetic and technological challenges in the past.

Several years ago, while collecting materials for Linotype: The Film I came across these strange code words in the Linotype “Big Red” specimen book. After asking several Linotype enthusiasts, I was told that these were code words created to save money on telegraph fees.

Although it may be difficult to understand today; before email and online ordering, if you needed to purchase a new font of type from a foundry—and you needed it fast—you would send your order via a telegram to the company. And as with most bleeding-edge technology, sending a telegram didn’t come cheap.

Cheating the System

Since telegram companies such as Western Union charged by the word, telegraphic commercial codes were created for all sorts of industries which allowed customers to ask complicated questions or order items with a minimum number of words to keep costs down.

As I learned by reading this Wikipedia article, soon after the invention of the telegraph, the first commercial codes were developed and several common code books were published with names such as Acme Code, Whitelaw’s Telegraph Cyphers, and Weather and Famine Telegraphic Word-Code.

Of course, the telegraph companies did not like customers undermining their fees and attempted to regulate that only real words in certain western languages could be used. However, code words were already in common use and in 1903, they removed their opposition and allowed any pronounceable word, no longer than 10 letters in length.

Clarifying Meaning

Reading the chapter on non-secret codes in The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing, the author explains that it quickly became obvious that code words needed to be fully nonsensical to avoid confusion with real words or directives in telegrams. If a code word was too close to another word, it was possible that a mistake could be made in reading or transmitting messages.

In one extreme case that went all the way to the Supreme Court, a simple mistake of adding a dot by the telegraph operator (accidentally changing the code word “bay” to “buy”) meant that 300,000 pounds of wool was purchased in error for a Philadelphia wool dealer, costing more than $20,000. The dealer sued Western Union, but in the final decision he was only awarded the cost of the telegram itself: $1.15.

Keystone Kode

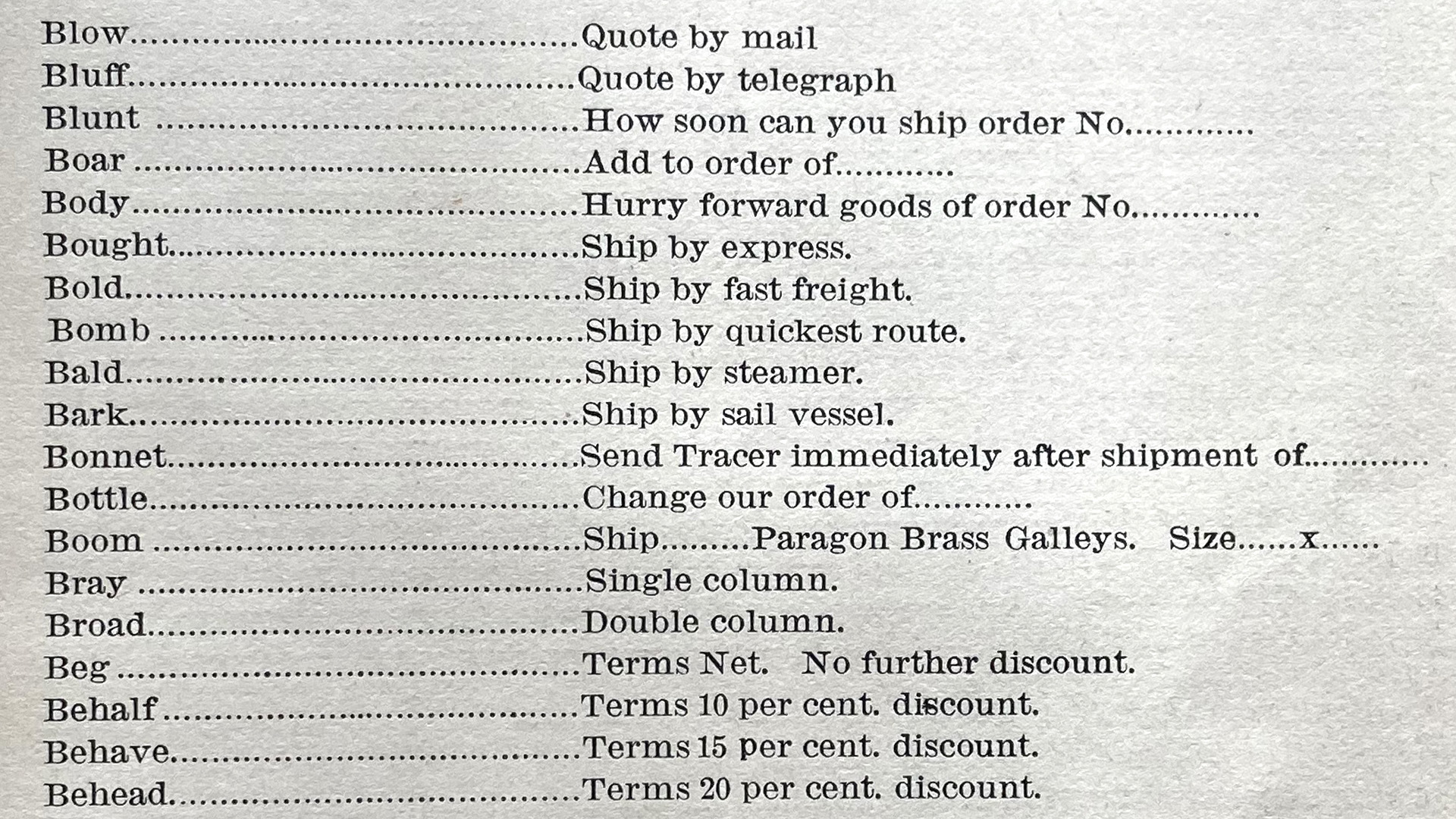

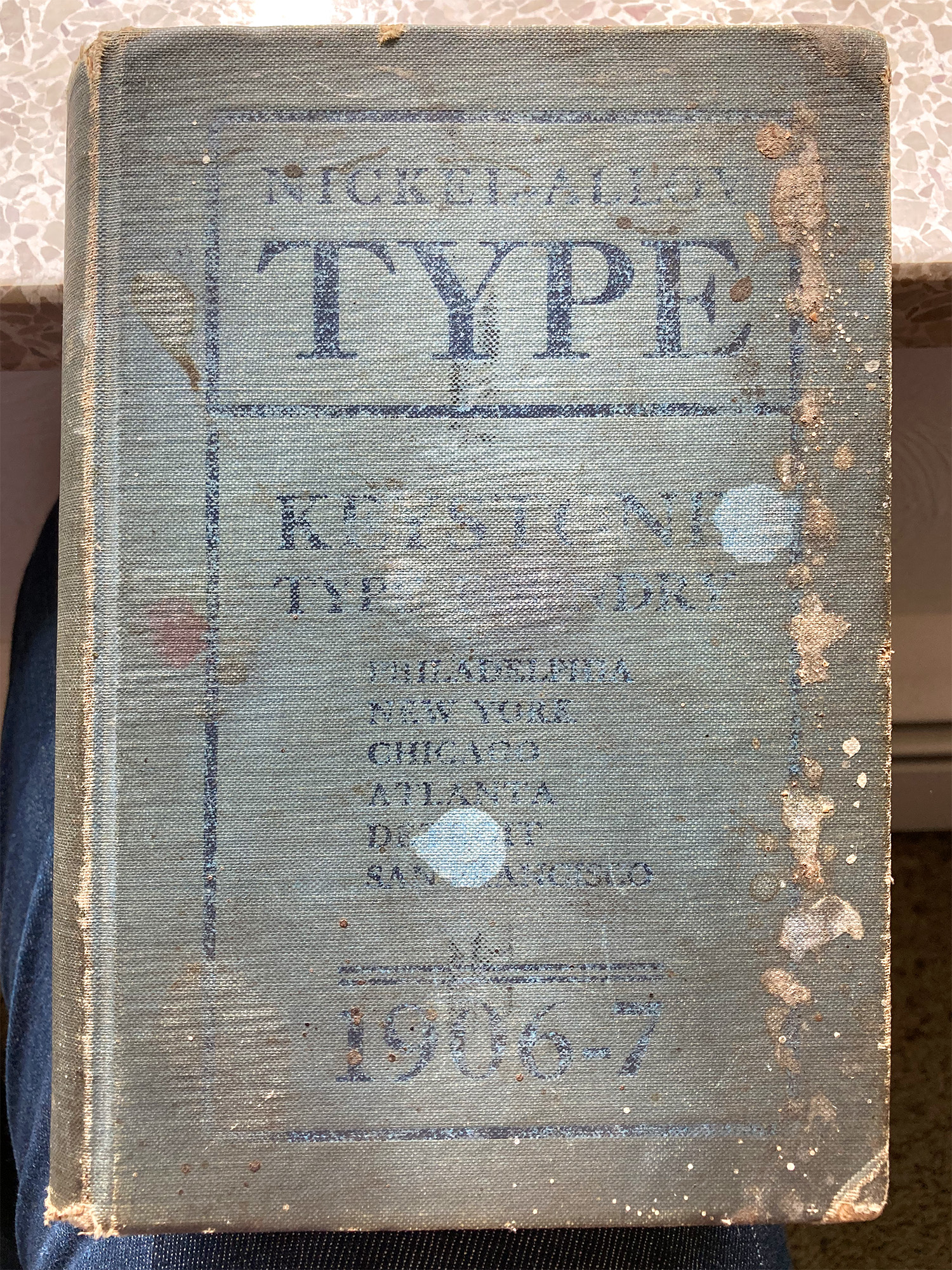

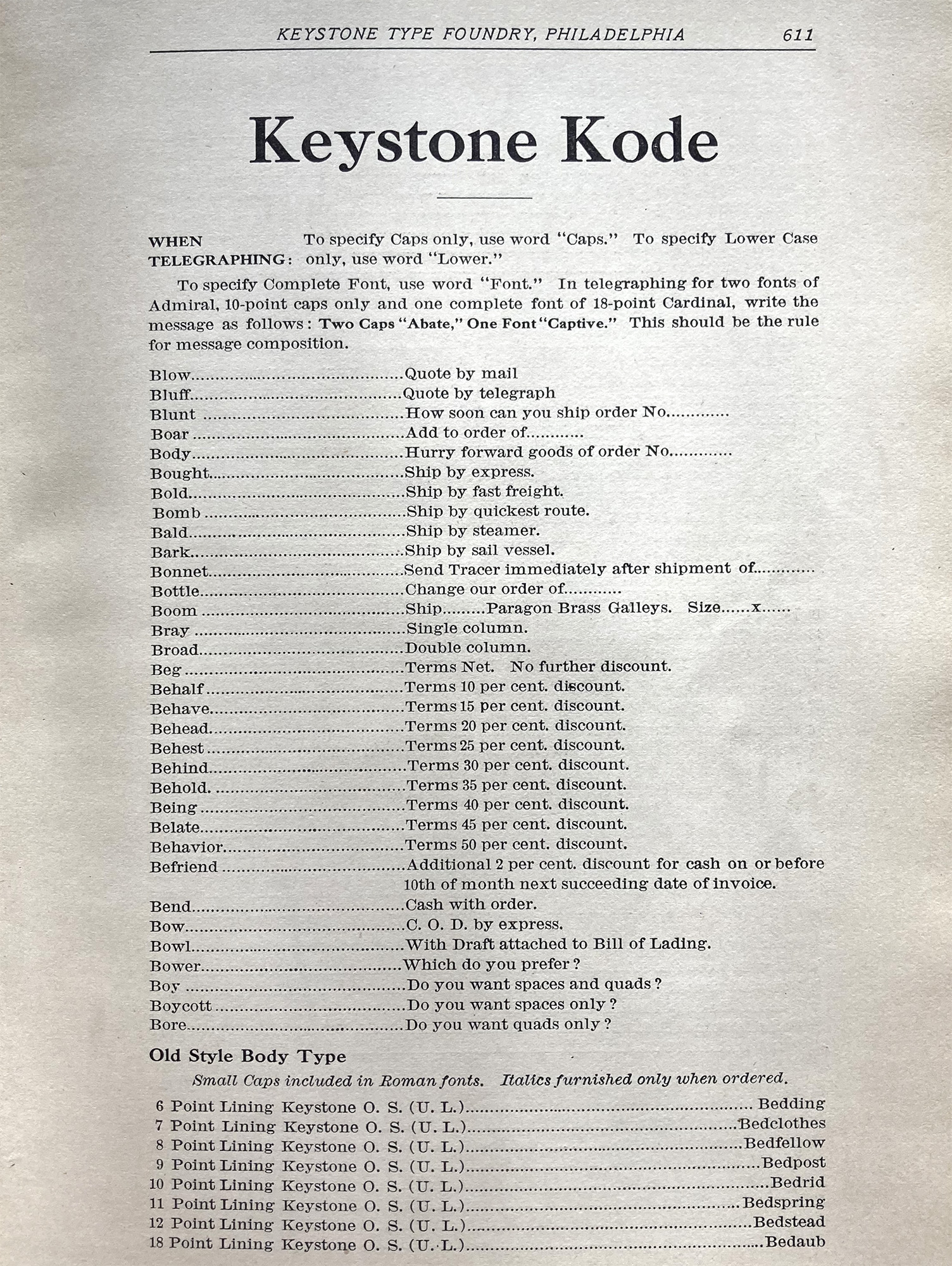

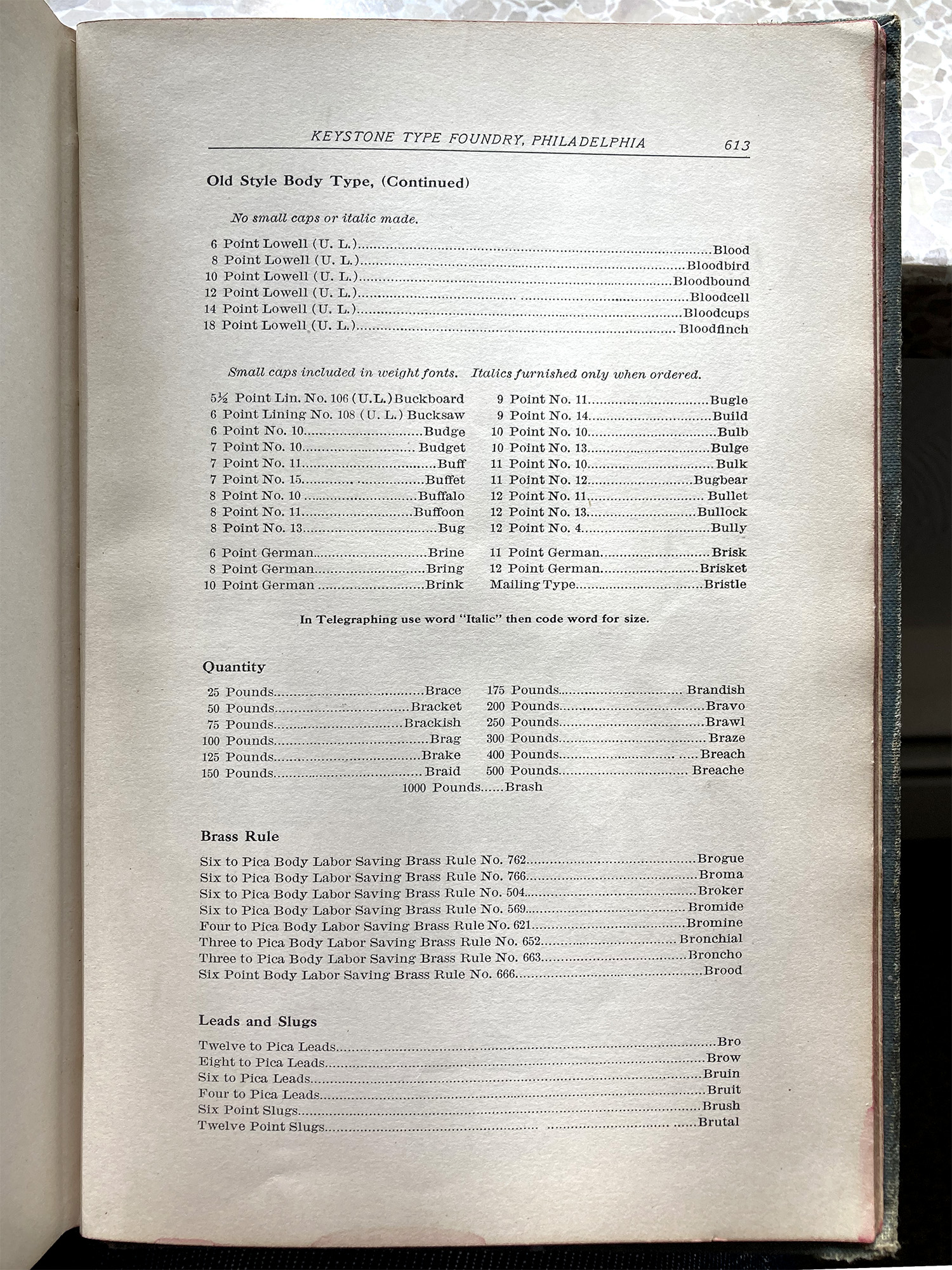

It was typical for many companies and industries to create specific commercial codes for their needs. The Keystone Type Foundry of Philadelphia, PA printed instructions and codes for ordering their type in their 1906–7 specimen book.

So, if a customer wanted to inquire about the price of a complete font of Lowell in 12 point and 75 pounds of Twelve Point Slugs shipped by express, this is what they would telegram: “BLUFF, One Font BLOODCELL, BRACKISH BRUTAL, BOUGHT.”

Hilariously Specific Codes

Here’s a list of my favorite codes that I came across while researching, which I feel needs to be shared:

- IDDOG - Ship in port, all hands down with scurvy

- DIONYSIA - Amputation is considered necessary

- SWAMK - Join us in prayer for funds

- VAOIK - Forced landing account engine trouble

- BUKSI - Avoid arrest if possible

- WUMND - Have every reason to believe oil will be struck

- COGNOSCO - Dining out this evening, send dress clothes here

- ABDIC - Extra quality, very fat and white

Deciphering the Codes

I’ll leave you, good reader, with the first paragraph of a humorous article written in the July 28, 1934 issue of The New Yorker by Jack Littlefield entitled “Melancholy Notes on a Cablegram Code Book”

Every time I receive a cablegram in code, I have the same feeling of pleasurable excitement. There is the familiar envelope lying on my desk, marked “Cablegram: Urgent.” I rip it open and discover inside the single mysterious word BIINC. The message is from our Venezuela office. Visions at once loom of secret documents, beautiful women, and dark Latin-American intrigue. Then I turn to my code book and find BIINC: What appliances have you for lifting heavy machinery? This sort of thing can be very debilitating.